Factors Influencing the Style and Quality of Wine

Clarification

After fermentation and before bottling, wine must undergo some clarification and stabilization.

Clarification

Before bottling, the wine must undergo some clarification and stabilization to remove solids, sediment, and microbial contaminants. This may include dead yeast cells (lees), bacteria, tartrates, proteins, pectins, tannins and other compounds, as well as pieces of grape skin, pulp and stems.

Clarification stabilizes the wine and improves its clarity.

The primary clarification methods are:

Sedimentation:

When solids in the wine settle at the bottom of the fermentation vessel due to gravity.Racking:

Moving wine from one vessel to another leaving sediments behind.Fining:

Fining agents are added to the wine to bind with unwanted particles.Filtration:

Passing the wine through a filter to physically remove suspended solids and microbes.Depth Filtration:

Trap particles inside a deep filter while wine passes through.Surface Filtration:

Trap particles on the surface of a filter like a coffee filter.Stabilisation:

Ensuring the longevity and quality of wine after bottling.

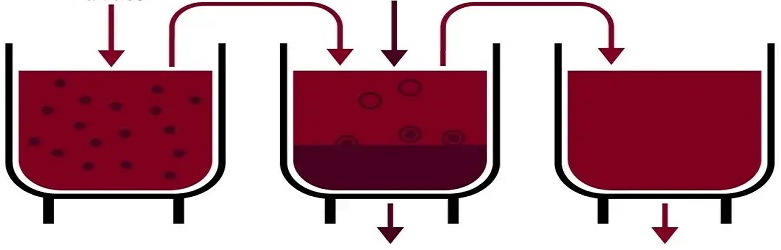

Sedimentation

Sedimentation is the process where heavy particles in the wine known as lees (dead yeast cells, grape skins and organic matter) settle at the bottom of the fermentation vessel due to gravity.

Sedimentation is a natural process that does not require additives or mechanical intervention. It is a slow process, taking weeks or months, which may not be suitable for all schedules. Additionally, it does not remove all suspended particles, so further clarification might be needed.

Sedimentation can enhance the flavor and texture of the wine due to contact with the lees, especially in white wines like Chardonnay, where lees aging can be desirable.

For some fine wines, racking is the only clarification that is used.

Racking (Soutirage)

Racking is the process of moving wine from one container to another, using gravity.

Alexis Lichine's Encyclopedia of Wines and Spirits defines racking as "Siphoning wine off the lees into a new, clean barrel or vessel" (a pump can be disruptive to the wine). Racking is known as Soutirage in French, Abstich in German and Travaso in Italian.

Racking helps in clarification and aids in stabilization. The process is often repeated several times during the maturation of wine.

Fining

Fining is the process where substances (fining agents) are added to the wine to bind with unwanted particles, forming larger clumps that are easier to remove:

Fining agents (see below) are introduced into the wine to attract particles like proteins, tannins, or compounds that cause haze, bitterness, or instability in the wine. Once bound together, these larger complexes either settle out of the wine through sedimentation or are removed by filtration.

Fining can be a quick and effective way to remove unwanted elements from the wine, improving clarity, flavor, and stability. It can also help adjust the tannin levels and astringency in the wine.

The choice of fining agent can affect the wine's flavor and mouthfeel, sometimes stripping desired components along with the undesired ones. Additionally, some fining agents (e.g., those derived from animal products) may not be suitable for vegan or allergen-sensitive consumers.

Fining Agents

Bentonite

A type of clay that absorbs unstable proteins.Egg white

Removes harsh tannins and clarifies the wine.

As an allergen, it must be listed on the wine label in EU.Casein

A milk protein that can clarify and remove browning from white wines.

As an allergen, it must be listed on the wine label in EU.Isinglass

Fish bladders that clarify white wines and give them that brighter quality.- Charcoal

Removes brown colors and off-odors.

Charcoal can over-fine. It can remove desirable aromas and flavors.